Another page has turned and the 2012 Hermosillo Book Fair has come to a close. The Fair, which ran from late Oct. through early Nov. brought together lovers of words and literature in a series of conferences, events, and a flurry of activity. Here are excerpts from notes sent to us by authors and fairgoers alike from the 2012 event. Full articles in Spanish may be found under the Soñar que Vemos tab of author Carlos Sánchez in our Rocky Lounge.

Orbit of elements: Spaces of emotion

Excerpts from Carlos Sánchez

I submerge myself in the pages. The reading suddenly turns me into a child with eyes closed, I squeeze my eyes and find myself directly and unyieldingly with the senses. And there I am, in an exercise of introspection. I remain in this zeal of feeling everything, watching me travel through the interior just as a spectator heading to a seat with his name on it to observe the film of one’s life, to feel the heartbeats of one’s story.

I submerge myself in the pages. The reading suddenly turns me into a child with eyes closed, I squeeze my eyes and find myself directly and unyieldingly with the senses. And there I am, in an exercise of introspection. I remain in this zeal of feeling everything, watching me travel through the interior just as a spectator heading to a seat with his name on it to observe the film of one’s life, to feel the heartbeats of one’s story.

Sentido is the name of the first poem within these pages that is a book with the surname Orbit of the elements. Orbit, name with such finesse and certainty of the liberty to construct poetry. I say liberty because Ignacio Mondaca, the poet, Nacho, author of this orbit, suddenly jumps over the bars – or rather, he does not jump over them but recounts all the references poetry possesses and decides, I am not sure when or at what moment, to saturate words in prose and they are a poem. Many poems. …

Here, I as a reader, express gratitude for this book of poetry that from its first text has shown me that within myself there is an orbit. Gratitude for these elements that arise in prose to construct poetry.

The best journalism being done in Mexico is by women

Excerpts from Carlos Sánchez

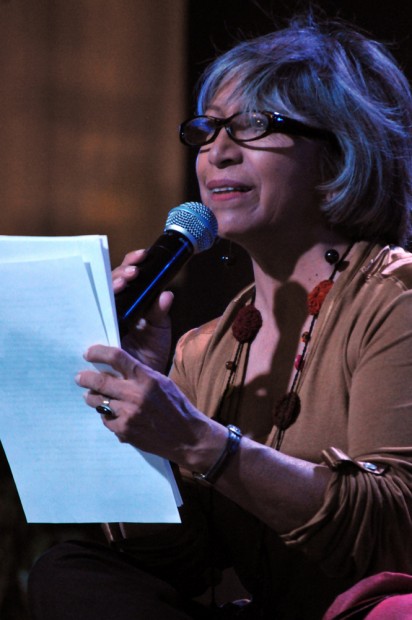

Elvira García is an Hermosillo native who resides in Mexico City. She is a journalist, runs a radio program, and has published various books, the most recent of these being Ellas tecleando su historia – entrevistas con mujeres periodistas (ed. Grijalbo, 2012) (They [the women] typing their story: interviews with women journalists). This was the reason for her visit to the City of Sun, and that which she presented at the 2012 Hermosillo Book Fair.

Elvira García is an Hermosillo native who resides in Mexico City. She is a journalist, runs a radio program, and has published various books, the most recent of these being Ellas tecleando su historia – entrevistas con mujeres periodistas (ed. Grijalbo, 2012) (They [the women] typing their story: interviews with women journalists). This was the reason for her visit to the City of Sun, and that which she presented at the 2012 Hermosillo Book Fair.

In Ellas tecleando su historia the voices of Ana Lilia Pérez, Lilia Saúl Rodríguez, Beatriz Pereyra, Marcela Turati, Anabel Hernández, Dolia Estévez, Adriana Malvido, Alicia Salgado, Blanche Petrich, Sara Lovera, Ximena Ortúzar, Anne Marie Mergier, Dolores Cordero and Stela Calloni are present.

García explains, “Basically [the themes within the book] are those that they themselves have explored in their work, they are a representative breadth of women’s paths in Mexico throughout fifty years; the youngest of the interviewees in my book is thirty-four and the oldest is eighty-four. Within this wide range there are three or four generations represented therein and those who have lived journalism as war correspondents, such as Dolores Cordero during the time when there were few women journalists and when women were received to write about social items, entertainment.

What I do is a selection of women, representative of journalism that opened paths to women themselves and that broadened the vision of media, particularly in print; the topic of women did not exist, we weren’t newsworthy, unless you were Elizabeth Taylor and remarrying once more, or because a woman had killed her husband, yet women were not news from the point of view of what women do, their ambitions, conflicts. All of that began in the 70s with the feminist movement that came from the U.S., birth control pills – as all these themes were about women, they began to be part of mass media, but also because we the women were now there.

What happens to you when you learn about one of your colleagues being killed?

– First and foremost, indignation, concern, and a need to raise my voice and say the government really needs to do something not just for women journalists, but for all journalists. In this sense I don’t think one should only talk about women, we must talk about everyone in the field in a way to tell of the consequences of drug-trafficking. I get concerned and I am in solidarity with them, this field has become dangerous…and the best journalism being done in Mexico is being done by women.

Humor as a mechanism of Defense

Excerpt from: Carlos Sánchez

Ricardo Cucamonga of Sonora is a humorist, although some say he is a writer. When the latter happens, he explains, he puffs up “like a peacock, because that’s pretty cool.” Cucamonga was at the 2012 Hermosillo Book Fair to present his book Cómo casarse tipo bien (How to marry well).

His character, Cindy la Regia (Cindy from Monterrey) has been a project of his for eight years. He explains this in the preamble to his book, “It is a comic strip found in alternative magazines in Monterrey, and what was originally a phenomenon on social networks then became viral, through mail, and now on twitter and facebook, and now editorially. I published my book with Random House Mondadori in February and it is one of the most read books this year, I’m thrilled!”

In explaining his work, Cucamonga states, “I do a particular type of humor, and my background as a humorist, as a graphic artist and as a writer cannot be explained without the use of internet. I was very lucky precisely here in Hermosillo where I lived from ’95 –’97. I learned about the internet and my mind exploded, I said this is wonderful – to see people that in your lifetime you never would have seen in any other way, work of others, and contacting people from the other side of the world. That is when I began doing my humoristic proposals – I’ve always used humor as a defense mechanism. I believe humorists are disappointed romantics, what we don’t understand about the world and that which seems incomprehensible, chaotic – we turn it into comedy and tell jokes when confronting the storm.”

A world without horizons

Excerpt from Imanol Caneyada

The world is not as it was. Without the certainties of science or faith as the pillar of our acts, postmodernity is firmly established, cancels the future, and we have no further remedy than to live intensely in the present, in the here and now, filling the void with material satisfaction. Thus, the future will not belong to anyone.

The world is not as it was. Without the certainties of science or faith as the pillar of our acts, postmodernity is firmly established, cancels the future, and we have no further remedy than to live intensely in the present, in the here and now, filling the void with material satisfaction. Thus, the future will not belong to anyone.

Seated at the edge of the stage of the principal forum of the Hermosillo Book Fair, on the edge itself of the abyss of a time in which absolute truths have died and relativism surrounds us to perceive reality individually, Oscar de la Borbolla presented his most recent novel El futuro no será de nadie (The future will not belong to anyone). Between irony, sarcasm, and trickery, he told us the world has lost its horizons. …

De la Borbolla says he chose love to reflect upon postmodernity because the majority of people are not interested in science, religion, and philosophy. He says he chose love because in its current and modern expression, we can find within it the symptoms of our time.

The novelist arrived at El futuro no será de nadie following a long journey from his childhood, when the viciousness of the barrio he was born into made him close himself in at home and seek refuge in a small and bizarre library, whose titles included everything except anything apt for minors. With his corrosive, fantastic, black humor and exact phrase style, Oscar de la Borbolla lays out within this novel the discouragement of the present, the anxiety of romantic love, the exacerbated hedonism of a society which in its depth knows the future will not belong to anyone….