By Guillermo Munro Palacio

On the morning of December 24, 1952, I woke up missing the songs my mother would usually wake us up with daily. I went to look for her in the kitchen, where I found her measuring coffee into the coffee pot. “Your father didn’t arrive,” she said. There was sadness in her voice. I went back to the cot where my brother René was still sleeping, I shook him and said, “My dad didn’t come back.” “Probably later,” he responded, turning over and covering himself with the blanket. My five-year old brother Neto was sleeping in my parents bed.

I made my way to our improvised Christmas tree; a pine branch covered with cotton balls that looked like snow, and on the top a star made with silver paper taken out of cigarette boxes that we collected precisely for this purpose. I picked up a few cotton balls off the ground and placed them once again on the tree.

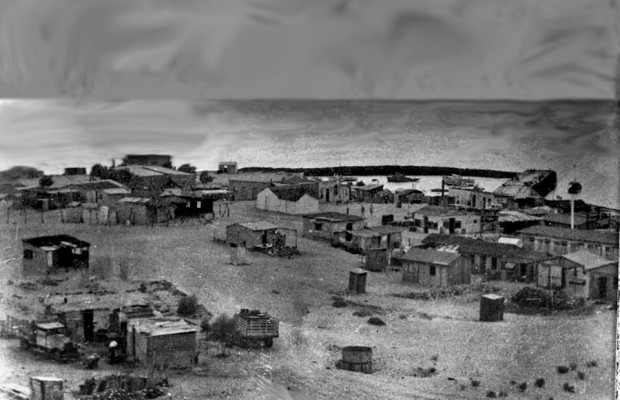

“Come on, get up!” I told René, “Let’s go to the docks.” We sat at the table and finished up our hot oatmeal topped with cinnamon and Carnation milk, and left without saying anything to our mother. It was a very cold morning; we wore our wool checkered coats and nearly matching caps with ear flaps. We fastened our coats and strapped the ear flaps under our chins.

We lived on Calle 16 de septiembre, and as we left we ran into Chico Angulo and Oscar Carrasco. “Where are you going?” Chico asked us. “To the docks, to see the boats come in and ask if they’ve seen my dad’s boat.” “What are you getting on Christmas morning?” “Cowboy outfits, with pistols and sombreros,” answered René. “Where do they sell those?” asked Oscar. “My mom ordered them from a catalogue, from Aldens,” I answered. “No, from Sears,” said René. “They already came in, they’re hidden and locked away in the closet,” I added.

We kept walking. Along the Chinesca alley we ran into Temo Quevado on the way to the docks. Some of the ships that had come in the night before were unloading shrimp. There was El Bitín Borboa and Lencho García, Manuel and Martín Angulo and Chico’s brother, Julián. Another boat was unloading totoaba. El Temo and Julián went back for some knives to cut the fish cheeks and throats, which are really tasty when fried in lard. The kids, and some of the adults, would take off the throat and cheeks before they were thrown out. Others would take a head or tail in order to make broth.

René and I climbed into a panga that was coming and going from one of the boats. There I asked the boat captain if he had seen ‘Alberto A,’ which was the boat my father captained. “We saw it in front of Puerto Libertad. It seemed to have problems with its rudder,” said the captain. René came out of the ship’s kitchen, clutching a can of condensed milk. He passed it to me and I took a long sip.

On our way back, we turned toward the Goya movie theater, just as we did daily to look at the billboards. It being Christmas, there was a 2 for 1 special. There were two American films, one with Humphrey Bogart and the other with Audie Murphy.

Back at home, we told our mother about the problem with ‘Alberto A.’ “Don’t leave again without permission,” she scolded. “I need to send you to the store for some things.” She went to the dresser, pulled out money from one of the doors and instructed us, “Bring 6 kilos of masa from Beto Mitre, and 2 kilos of meat from Roberto Guzmán, ask for the scruff.” Then she gave us a list of everything she needed for the tamales and buñuelos. “Go with Chindo and with El Faro for the rest. On your way back, go by Limón’s gas station for oil for the lamps and with Jesús Cornejo for wood for the fire.” Our fire pit was a square can.

“Let’s go up the hill first,” I told René, “From the top we can probably see dad’s boat.” We sat on huge rocks in front of the sea. Up there you could feel the bitter wind even more so as it burned your face. We peered out to the horizon, but couldn’t see anything. Down below, on the rocks near the Hotel Cortez, there were some sea lions. It was so cold up there so we quickly made our way down to the stores. We got to the bakery, run by Jorge’s dad and El Tilico López, and bought two loaves. Yolanda, the sister, tended to us.

“Let’s go up the hill first,” I told René, “From the top we can probably see dad’s boat.” We sat on huge rocks in front of the sea. Up there you could feel the bitter wind even more so as it burned your face. We peered out to the horizon, but couldn’t see anything. Down below, on the rocks near the Hotel Cortez, there were some sea lions. It was so cold up there so we quickly made our way down to the stores. We got to the bakery, run by Jorge’s dad and El Tilico López, and bought two loaves. Yolanda, the sister, tended to us.

That night, el Serapio, El Teodorín, El Monchi Robles, Rafael Luis Sotelo along with other kids and us went to the movie as soon as it opened. Before that, Serapio and I had gone to the docks with the hopes of spotting ‘Alberto A’, but nothing. There were kids everywhere with their lamps and setting off fireworks, Octavio Oscar Ortega, Armando Valle and Jorge Ren among them. Though we were used to it, you could still feel the vibration from the diesel electric plant, with the humming motor in the background. When we left the movies, I convinced Serapio to go back and check the boats again. I had to offer him champurrado and an empanada from Doña Beatricita’s restaurant just to convince him. Later he told me his mom, Chata Olivarría, had punished him for going to the movies and then the docks without permission.

Along the way to the docks, I prayed an Our Father that my dad would be back at the port. As there was no electricity and the only lights were gas or oil lamps, I was awestruck by the Milky Way and the millions of stars in the sky. All the streets smelled like tamales and menudo. That’s because at the majority of homes people were cooking outside. You could hear loud voices and laughter from men gathered around fires, warming up with sips of tequila, telling interesting tales that only fishermen know how to tell with style. The dock was calm. Some fishermen who lived on the boats were singing and laughing happily.

My mother was furious when I got home. She had us all kneel down and pray for the safe and healthy return of dad. We ate in near silence, concerned. The tamales were delicious, accompanied by “a little something to warm you up” of cinnamon with fruit. The buñuelos bathed in hot honey were phenomenal! We hardly spoke. One by one we peeled off to go to sleep.

In my deepest sleep I heard voices; I got up and saw two fishermen from the boat’s crew helping my father to bed. He was shaking with fever. My mom gave him a hot drink with tequila. The crew said they had lost the rudder and my dad dove down, trying to find it in the icy waters of the sea. They said thanks to my dad’s abilities, they were able to get back by using outriggers and nets to direct the course. “He didn’t want us to help him. He spent the whole time on the maneuver,” explained the fishermen.

I went over to him and hugged his trembling body, “I went to the dock many times to see if you were here, at night too,” I told him. He made a gesture with his face, appreciating what I had said. His teeth were chattering. He put his arm around me; said nothing. He never really said anything. He was a man of few words when overtaken by emotion. I went back to my cot; René opened his eyes, “Is it Christmas?” he asked, only half awake. “Not yet,” answered my dad, “Go to sleep so you can wake up early,” he said with his shaky voice. René looked at me and said, “See, didn’t I tell you he would get here later?” René was 7, I was 9, and that was Christmas morning 1952.